Are You There Godzilla? It's Me, Carlo

As a fan of high concept genre, I’ve always had a bit of a fascination with kaiju (lit. strange beast) movies, but it wasn’t until a short while ago when I watched Toho’s King Kong duology that it totally clicked for me. It sent me down a gargantuan spiral of endless Godzilla sequels, and while I enjoyed my time with them on a large enough scale, I don’t plan on boring you with the minutiae of every entry. At worst they’re glorified wrestling matches between soon-to-be new toys. When they’re good, however, I wanna say the sky is the limit, but even as a metaphor that might be short-changing them.

A quick history lesson teaches us that Godzilla (1954) was Japan’s post-traumatic reaction to the nuclear bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Even if they intrinsically follow the same narrative – intertwining of large-scale destruction, and smaller, human conflict – there’s a pretty noticable, and jarring shift in tone once they started re-branding Godzilla. Suddenly, in the '60s, he became a goofy anti-hero. Much like the mourning process anticipates, there eventually comes a time to move on and transition your grief to the next stage in a productive way. Now I’m not saying movie studios had any such noble intentions, but sometimes happy accidents take form unknowingly.

The thing about happy accidents, however, is that they’re accidental (no foolin’). Now you have to understand that Japan is a country steeped in tradition and, rather than letting accidents happen, they often prefer to stick to the safe and dependable. Experiencing all of the Godzilla movies in quick succession, then, does incite a feeling of reliability. Even when Godzilla gets beemed off into outer space to fight a three-headed, lightning-spewing dragon on some made-up planet in Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965), there’s a margin of safety built into it and a sense of comfort in knowing what you’re getting. Thankfully, seeing how there are more than 30 of 'em right now, there were bound to be at least one or two happy accidents along the way.

Most of the Godzilla movies in this initial “Showa” (’54-’75) period in Japan were directed by Ishiro Honda. After four sequels between 1962 and 1965 his formula (along with Godzilla’s rubber costume) was starting to show the first signs of wear; so Toho decided to hand the reigns over to a guy called Jun Fukuda. Now, if the thought of flying saucers and victory dances in outer space still sound too serious for you, wait ’til you get a load of this guy. Ebirah Horror of the Deep (aka Godzilla VS. The Sea Monster, 1966) and Son of Godzilla (1967) are the ultimate evolution in silly and colorful – exclusively taking place on a tropical island, featuring a hefty wardrobe of Hawaiian shirts, knock-off Beach Boys tunes, and devoid of any sort of mass destruction. Toho might have wanted a fresh take on Godzilla, but these weren’t exactly that.

As we enter the '70s with already the 11th entry, classic Godzilla is about to hit an unwanted peak with Godzilla Vs. Hedorah (aka Godzilla VS. The Smog Monster, 1971). I say unwanted, because one-time director Yoshimitsu Banno’s psychedelic stint was so far removed from Toho’s comfort zone that he was accused of ruining Godzilla forever. Dramatic much? Considering he filmed it in little over a month with one small team and an even smaller budget, the end result is downright awe-inspiring. Desperate situations call for creativeness, and all that.

Even if you don’t have any interest in these movies (firstly you must be really bored to have gotten this far), Godzilla Vs. Hedorah is the one I can safely recommend to anyone with an omnivorous interest in cinema. It’s a return to the terror of the original, but not in an unnerving way; it’s goofy but it doesn’t feel aimed at children at all. Story-wise it’s the exact same thing you’ve come to expect, and even borders on being “traditional” Monster of the Week. What sets it apart, however, is a tone that’s neither here nor there, yet charged with very distinct auteurism. I will say that having an understanding of what makes for a standard Godzilla movie helps put in perspective the extent to which things were changed up, but just to give you an idea: animated segments that look like something out of Yellow Submarine aren’t the norm' (but very much welcome).

Look, I get it, Toho was in the business of making movies and turning a profit. Audiences expecting a simple and straightforward monster flick didn’t respond well to Banno’s vision, and despite it having gained a cult-following over the past few decades, there’s still a degree of polarisation between fans. Nobody likes change until they realize things have gotten stale and predictable, and even then you can’t just hit them in the face with it. Alas such was the way of things, as Toho quickly resorted back to Jun Fukuda who at least knew how to play it comparatively safe.

It wouldn’t be until 1975 (and four more entries) when Godzilla would enter his first official hibernation, to usher in the Heisei era in 1984’s The Return of Godzilla. But as I’m currently on doctor’s orders to stay away from any more heavy kaiju binging to avoid overexertion, I haven’t ventured down that path just yet. As time goes by Godzilla has had trouble recreating the same impact it once had. Even if the originating themes of global pollution are more relevant than they’ve ever been, there’s something charming about the old campy, rubber-suit sequels that is impossible to recreate. Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla (2014) is a perfectly functional movie, and not much worse or better than most of those, but I’m not really looking for hyper-realism in a Godzilla movie. Nor setting up the next five movies, or anywhere else for that matter.

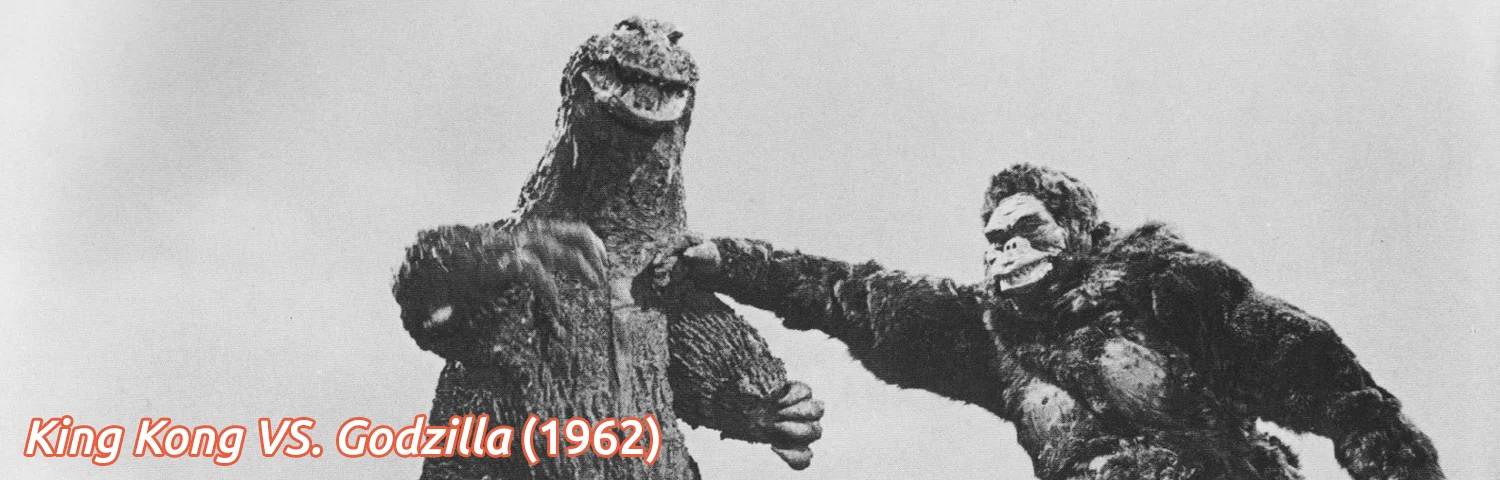

Highlights of the Showa-era Godzilla franchise include: Godzilla (1954), King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), Ghidorah the Three-Headed Monster (1964), Godzilla Vs. the Sea Monster (1966), Son of Godzilla (1967), and Godzilla vs. Hedorah (1971).