It's All Relative: Movies About the Inherent Dysfunction in Families

Family values are often touted as the cornerstone of society. We’re told that being part of a family means unconditional love and support, despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Plenty of people are estranged from family members, hate their parents and siblings, or just live with toxic versions of what familial relationships are supposed to be. The fetishization of the family unit is only now beginning to get picked apart as people are becoming more honest and aware of the skewed, unfair dynamics that can play out within an insular group. Not only are we as a whole opening up the definition of what it means to have a family, we’re also seeing some interesting portrayals of what families are and some real introspection on what counts as functional.

Captain Fantastic (2016) is a great jumping off point for a discussion about what it means to be born into a group and how we view parent-child relationships. Ben Cash (Viggo Mortensen) is a dad raising his group of kids off the grid and out of civilization. At the start of the movie, he receives news that his wife Leslie (Trin Miller) has died in the hospital. As Ben gathers the clan together to attend her funeral, we as the audience get to see the paradox of who children actual belong to play out.

Ben has a written will that says Leslie wanted to be cremated, but her parents want her to be buried. This is a point of contention that kicks off a lot of the action in the third act of the movie, while also centering the moral question of autonomy. Ben’s children are cared for, well-educated, and self sufficient. They are also not allowed to partake in anything Ben doesn’t care for, be that public school or junk food. Yet his wife’s parents are willfully ignoring their late daughter’s wishes because they think they know better than she or her husband does. Both sets of parents are making decisions based on their own skewed perspective and fall into the same trap of accusing the younger generation of not knowing what they’re doing.

Tensions begin to build in the family when it’s discovered that Leslie was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and was hospitalized for mental health reasons. Ben admits to supporting her decision to go off her meds, as well as not supporting her decision to go back to civilization and get help when she felt her situation was worsening. He and Leslie’s dad share a similar sense of always being in the right, even when they are seeing the destructive outcome of their beliefs. For the children being pulled along, it’s confusing and frustrating.

Parents at their best are genuinely trying to protect their children. But sometimes they themselves are the source of problems, even when they’re doing what they think is right. Like the patriarch of Captain Fantastic, the father in the documentary The Wolfpack (2015) believed that his unorthodox approach was correct, and the restrictions placed on his children were completely acceptable.

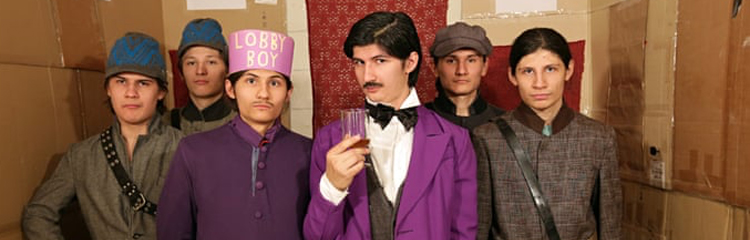

The Wolfpack follows a group of brothers who have been cloistered away in a Manhattan apartment for their entire lives. Their biggest window to the outside world is movies, and they devour them endlessly. They reenact their favorite scenes, memorizing scripts and character attributes as if they were classically trained actors. In their home, their father is a controlling alcoholic who dreamed of success and fame in the music industry; their mother, on the other hand, seems absent-minded and easily manipulated. She, along with the boys, is not allowed outside of the apartment.

Surprisingly, the boys are all well adjusted. One of them even comments that he knows the difference between violence in movies versus violence in real life. Because of the core group they’re able to create within the family, the boys have a sense of community and support that they might not have without one another. By the end of the documentary, the father has agreed to let the boys branch off into their own lives, and the mother has reached out to her own parents in Wisconsin, claiming it’s been close to 20 years since they’ve spoken.

The relationship between parent and child is already a complicated one, with its inherent power imbalance and the nonconsensual nature of existence. Movies exploring that dynamic often question who children really belong to: themselves, their parents, or society as a whole. A less probed topic is the hierarchical quality of having siblings.

In The Midnight Swim (2014), three sisters return to their recently deceased mother’s lakehouse to get it ready for sale. The house is on Spirit Lake, which is known for being so deep that no diver has been able to find the bottom. The sisters’ mother is believed to have died during a nighttime dive but her body hasn’t been recovered. Throughout the week that the sisters are there, strange subtle things are happening. June (Lindsay Burdge) finds weird footage on her camera, while the youngest Isa (Aleksa Palladino) discovers dead birds right outside their door every morning. They discuss an old myth about seven sisters that drowned in the lake, the belief being that the last sister can be summoned and will pull you under. The eldest Annie (Jennifer Lafleur) makes it clear she thinks their mother was foolish for going on a night dive alone. Yet, as the week progresses, all three begin to wonder if there is something to the superstitions surrounding the lake.

A low-key ethereal thriller, The Midnight Swim ultimately becomes a musing on reincarnation and the happenstance of birth. Before the conclusion is reached though, a close-to-the-bone family drama unfolds. Isa is a half sister to the other two, something mentioned in passing when Isa’s being prickly, and Annie had a fractured relationship with the mother that was never healed prior to her death. One of the most uncomfortable scenes centers on the three going through the mother’s clothes. When Annie does an impression of mother, it slides into a grotesque performance of the borderline emotional abuse she was put through. The other two are shaken from the incident, and Annie only stops when she sees what it’s doing to them.

June has a history of behavioral problems that we never fully know. As the bizarre happenings go on, the schisms between Isa and Annie close, and they both start to suspect June. Where once June and Isa were bonded due to their closeness to their mother, the dynamic shifts when it’s thought that June’s old patterns are coming up again. In a confrontation close to the end of the movie, June can be heard begging and weeping to her sisters like a teenager as they make plans to leave the house (and her) behind. June surrenders to the draw of the lake and is reincarnated alongside her mother.

One of the biggest influence factors in the concept of the nuclear family is tradition. For better or worse, families are about handing down cultures and traditions from one generation to the next. The stunning Mexican horror movie We Are What We Are (2011) takes the idea of a destructive culture being celebrated as tradition that bonds siblings in a nightmarish way.

We Are What We Are follows a fairly insular family whose father drops dead from an unknown cause in the opening scene. The mother Patricia (Carmen Beato), the daughter Sabina (Paulina Gaitan), and the two sons, Alfredo (Francisco Barreiro) and Julian (Alan Chavez), are at a loss for how they’ll survive. They are also specifically concerned about a ritual that’s approaching where they are meant to kill and eat a human. Throughout the movie, an investigation is going on surrounding the father’s death and a cold case that’s being reopened. A finger is found in his stomach during the autopsy, and his mysterious, sudden illness is tied to these cannibalistic behaviors. Despite seeing obvious consequences of what they’re doing, the family continue looking for a person for their ritual.

Like poverty, the family in We Are.. is locked into a cycle they can’t seem to break away from. It’s clear they live on the fringes with limited means–the human meat is as much sustenance as it is homage to a tradition. The children attempt to take on roles as shown to them, their few questions being answered with the trite “because I said so.” While being taught how an adult acts, they are still relegated to the intellectual role of children where their hesitance or attempts to help are seen as juvenile and insubordinate. This is a unit that has found a way to survive and will stay the course. The subtext in this superbly written movie is that they truly believe there’s no other option.

The definition of family is shifting in today’s lexicon, and that’s a good thing. Families are complicated creatures that we want to accept as simple because we frame so much as unconditional inside the concept. Families are always supposed to love each other, support each other, put up with each other. We want the face-value of family to be true, and not have to delve into power structures, egos, and the authoritative need for compliance. Yet there is a true weirdness to family. It’s in this weirdness that the best of these movies find fertile ground to take root, exploring what can happen inside core groups whose beliefs are left so completely unchallenged.